How was slavery introduced to Poplar Grove Farm?

The first people at Poplar Grove Farm were native Americans — probably the Patawomeck Indians. Over the years we’ve discovered arrowheads and other tools left here by these early people. We do not have any records showing that the Patawomecks lived permanently on Poplar Grove farm, though this was clearly part of their hunting ground.

The easternmost parcels of the original roughly 700 acres called Poplar Grove Farm were part of the 295,000 acres of land owned by Robert “King” Carter. “Slaves working under the supervision of overseers provided the labor on [Carter’s] plantations, and senior overseers with responsibility for several farms managed those overseers.” (Encyclopedia of Virginia, Robert Carter 1664-1732). The eastern half of Poplar Grove farm may have been worked by these slaves. The western part of Poplar Grove farm, which is still in the family, is hilly and not the best farmland. We do not know if Robert Carter’s slaves ever worked at this part of Poplar Grove Farm.

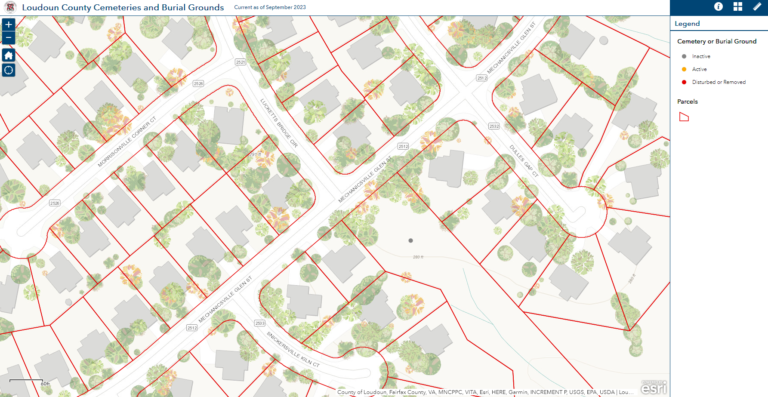

We do know that the first White people to permanently settle on the west side of Poplar Road at Poplar Grove Farm were Quakers who bought several farms along both sides of Poplar Road. They established a congregation called the Potomac Run Meeting in the mid to late 1700s south of the corner of what is now Chriswood Lane and Poplar Road where the Potomac Run crosses Poplar Road. King Carter’s profligate grandson, Charles Carter of Ludlow, had lost his land which included the eastern portion of Poplar Grove Farm, due to poor money management. Quakers purchased and settled the east and west sides of Poplar Road, which became Poplar Grove Farm. Quaker Friends are opposed to slavery, and there were no slaves on the Quaker-owned half of what became Poplar Grove Farm during the Quaker settlement. The Friends living along Poplar Road were skilled laborers who worked in the ironworks in Falmouth for John Strode, a Quaker. These individuals built a stone house and stone spring house on the west side of Poplar Road. They eventually left Stafford because the ironworks closed and due to pressures related to their opposition to slavery. Most of these Quaker Friends were in Ohio by 1814. I’m still tracking down the names of all the Quakers who lived on the west side of Poplar Road.

Portions of the east side Poplar Grove were purchased from Potomac Run Quakers named Jones beginning in 1807 by George Curtis, father of Sally Curtis, who was the first member of our family to actually live at Poplar Grove Farm. When Sarah “Sally” Curtis married James French in 1830, James and Sally set up house on the west side of Poplar Road in a Quaker-built stone house, which was torn down in the 1900s. The land was called Poplar Grove Farm after the unusual, non-native grove of Lombardy poplar trees planted here by the Quakers, and the entire area was called the Poplar Settlement by Stafford locals.

James and Sally were not opposed to slavery and did own slaves. At times James held more than 20 slaves. The Frenches enslaves more people than were needed to maintain their properties, so they rented these slaves to others. We know some of these slaves worked in the area around Richmond, Virginia. Betty Jones was the first slave we know lived at a Poplar Grove Farm. Betty had been gifted to Sally by her father, George Curtis.

TLDR: Slavery was introduced to Poplar Grove Farm by the James and Sarah Curtis French family when they began living on the farm in 1830, and slavery continued until the end of the Civil War in 1865.

Where did slaves live at Poplar Grove Farm?

Slaves lived in cabins on what is still called Cabin Hill, which is southeast of the family graveyard. It is one of the highest points of elevation on the Farm, and it has a commanding 360-degree view of the surrounding fields, barn, outbuildings, and homesite. Aunt Sally Lou told me there that in the 1860s there may have been as many as three cabins on what is still called Cabin Hill after the slave cabins that used to be in that location, which is the highest elevation and best view of the farm.

We have only one photograph of what may be a slave cabin. The image below, which must be dated before 1916 because the current gray barn was built in 1916, shows the original wooden barn at Poplar Grove. In the background of the picture, you can see Cabin Hill with a small white house atop it. In the photo, the house is in about the 3 o’clock position.

Below is a closeup of that portion of the image. Unfortunately, the photograph is badly damaged where the cabin is shown, but the cabin seems to be a wooden, two-story structure with a covered front porch. Cattle are seen resting in the field near the cabin.

This home is no longer standing.

What were the names of slaves who lived at Poplar Grove Farm?

Unfortunately, we don’t know the names of all the slaves who lived at Poplar Grove Farm. Union soldiers burned many records at Stafford Courthouse, so the slave death registry is incomplete. The farmhouse at Poplar Grove Farm burned down in 1935, and our family records are also scarce. Here are the names of slaves we have been able to track down in other records:

- Betty Jones

- Elzy Jones

- Julia Jones

- Washington Jones

- Sam Jones

- ___ Nelson ___

- The Parker Family

- Henry Cooke

- John Day

- Isaac ___

- Mary ___

I’ve collected the information we have on these slaves below:

Betty Jones

Betty “Bettie” Jones was given to Sally Curtis French when her father George Curtis died:

[I]t is my will and desire that my daughter Sally French, shall have the tract of land whereon she now resides called Popular Grove at five dollars per acre and negro girl Betty and her future increase at two-hundred dollars, she paying or receiving such sum as money as will make her portion equal with my other children.

Will of George Curtis French

Betty was married to a man named Elzy Jones and had sixteen children. Of these children, only ten reached adulthood. We believe her six children are buried at Poplar Grove Farm. At least one of her surviving children, Sam Jones, maintained a close relationship with the French family after the Civil War.

According to the 1880 Census, Betty was living with her son Samuel Jones in Hartwood on Shackleford Well Road near several other former Poplar Grove Farm slaves.

Elzy or “Elzey” or “Elsie” Jones (1805 – October 30, 1875)

Elzy was a slave whose parents were Alexander and Agnes Jones. He married Betty and together they had sixteen children, only ten of whom lived to adulthood. We believe their six children are buried at Poplar Grove Farm.

Sallie Fitzhugh told a story to Larry Evans of the Free Lance-Star newspaper about a seance in which Elzy Jones appeared. Apparently, an Englishman visited Poplar Grove farm for a week before 1837. He told the family that he had participated in a seance in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and during the seance, a Native American named Bright Eyes appeared and told the Englishman to return a tomahawk he’d found in Stafford County. The Englishman followed this request and walked all over Stafford County trying to find the exact location where he’d found the tomahawk years before. The Englishman also claimed that during the Pittysburgh seance a black man named “Uncle Elsie” had appeared. He asked the family if they knew anyone by the name Uncle Elsie, and the family confirmed that Uncle Elsie had been a slave at Poplar Grove Farm before the Civil War.

According to Library of Virginia; Richmond, Virginia; Virginia Deaths and Burials, 1853-1912, Elzey Jones, a laborer, married to Bettie Jones, son of Alex^r and Agnes Jones, died on October 30, 1875, at age 70 in Stafford County of kidney disease.

Julia Jones (January 20, 1852 – February 25, 1853)

Julia was the daughter of Elzy and Betty Jones. She died of whooping cough on February 25, 1853, at two years, two months, and five days old according to the Stafford slave register. This puts Julia’s birthdate at January 20, 1852.

Washington Jones (1851?-1919?)

Washington is listed as a child of Elzy (Elzey) and Betty Jones at Ancestry.com. He was born sometime between 1851 and 1865 and was married to Mary Francis Stewart or Steward on May 31, 1888. He named his first son “Elsie” after his father. He also had children William, Alfred, Minnie, and Martha. Washington lived near his brother Sam Jones, and the Hills, Parkers, and Browns in Hartwood.

There is a lot of discrepancy about Washington Jones’s birth and death dates. Washington’s birth date was reported as 1851 on the 1900 census, and as many other years in other locations. The death date on his headstone is definitely incorrect, as Washington appears in the US census as late as 1930. Despite these discrepancies, it’s easy to trace Washington by his family members, his wife’s name, and where he lives.

Unnamed female, (1856-1856)

Betty Jones’s unnamed female child died on September 20, 1856, at two months old of unknown causes according to the Stafford slave register. This puts the unnamed female’s birthday at July 20, 1856. We believe this child is one of Betty’s children who are buried at Poplar Grove Farm. Elzy is probably her father.

Unnamed female, (1857-1857)

A female slave died of smothering at Poplar Grove Farm in 1857 according to the Stafford slave register. The register does not list an age, death date, or parents for this child.

Nelson (1848-1857)

Nelson died of the measles on July 25, 1857, at 9 years of age. The slave registry does not list his parents’ names or his exact birthday. I believe that Nelson could be this boy’s last name, as there is a mulatto family living named Nelson living near the former Poplar Road slaves in Hartwood in 1880.

The Parkers, Henry Cooke, John Day, Uncle Isaac, and Aunt Mary

Sallie Fitzhugh (1886-1986) was interviewed in 1937 for a WPA survey of Stafford County. The history is now located at the Library of Virginia. Following is an excerpt from that interview:

The French family owned a number of slaves. A number of the slaves worked in Richmond and would come home once a year which was at Christmas. The slaves were named Parkers, Henry Cooke, Sam Jones, and John Day. Sam Jones lived to be very old, there is a picture of him taken after he was eighty-nine years old.

Mrs. French had four sons, three were old enough to enter the War Between the States. Hugh French joined the army in 1861, was stationed in Richmond, Va. and was a member of the Nineth Virginia Calvery [sic]. When he left for Richmond and entered the army he took his horse from from [sic] home. After he was killed his horse and clothes were sent home to his mother, Mrs. Sally French. Mrs. French knew if the Northern soldiers found the horse or her son’s clothes they would be taken from her. So the clothes were hidden in the bottom of a card basket and the horse in a wood of thick pine. A younger son and one of the sla ves [sic] would go and feed the horse once each day. They would go miles out of their way so that they would not be noticed by the soldiers. Thinking that the Northern soldiers had gone and would be gone for some time Mrs. French one [sic] of the slaves to go for the horse. No sooner had he returned with the horse then another slave called, “Northern soldiers are coming, soldiers.” Before the slave could get the horse back to the woods the soldiers had seized it and start-away. Mrs. French began to cry, and a daughter and the solders to argue and in the meantime the horse ran back to the wood. Later the horse was taken by the soldiers.

Interview of Mrs. Sally French Fitzhugh, April 13, 1937, by Julia Marie Heflin, 1937 WPA Report, Library of Virginia

Several days later the soldiers came back and searched the house. Aunt Mary, a slave, was working with the cards and had wool in the basket on top of the clothes. The soldiers searched eery place except the basket, they wanted to search this but Aunt Mary would not let them. This was the last time the Northern soldiers ever searched the French home. They often came back and camped.

Once the slaves saw the Northern soldiers coming, so they took the hens up in the attic and hid them. The soldiers searched every place except the attic. They were starting to leave, then the rooster crowed, this of course was a signal as to where the hens were hidden. They proceeded to the attic and caught every hen, only the rooster that crowed escaped, he was hidden behind a barrel.

The slaves asked their Mistress, Mrs. French, if they might have a dance during Christmas, and were given premission [sic].

Uncle Issac and Aunt Mary were the ones that wanted to have the dance for the slaves that were working in Richmond and were home for the holidays. The dance was going along nicely when the patarols [sic] came and broke it up. This frightened Uncle Issac and Aunt Mary so badly that Uncle Issac went running for Master James to come down and make the paterols [sic] get away as they had broken up their dance. Master James refused to go at first, but after Mistress Sally told him that she had given them the premission [sic] to have the dance he went to the cabin. He went in and said,”all the Rose negroes stand over against the wall and all the Ramey negroes stand on the left, and the rest of ypu [sic] negroes get away from here. They left as soon as the order was given, but the coming of the patarols broke up the dance for the night.

The Parkers

Regarding the Parkers, it’s possible two of the slaves were named William Parker and Frances or Mary Parker, as 1870 and 1880 census records show them living in Hartwood area with or next door to individuals sharing the last name of former Poplar Grove slaves. Other people living next door to the Parkers and one another are the Joneses, Hills, Browns, and Nelsons.

John Day

A John Day, age 28, was living in Hartwood in 1870. It’s possible this is the John Day who had been a former slave at Poplar Grove, especially since we can trace his mother through his death record to a Betty Parker, which is the last name of individuals we know were enslaved at Poplar Grove Farm. Also circumstantially, John Day lived in Hartwood, which is where at least some of the former Poplar Grove slaves moved after they were freed. In the 1870 census, John Day is with Lucy Day, 38; William Day, 18; and Otho Day, 11. William and Otho seem to be relatives of John’s, not his children.

John Day, 22, son of Austin and Betty Day, and Lucy James, 30, were married on January 25, 1868. Lucy was listed on that wedding record as a widow, which may explain the seeming age discrepancy.

By 1880 they’d had three mulatto children, L. Ida, Lottie, and Thorton (Lucy, 48, is listed as black and John, 39, as mulatto). Lucy died July 15, 1885, and was survived by John.

John last appears on the 1920 census living with his children Ida/Idia and Thornton/Tharnton. They were living next door to the Vines family, which Thornton married into in his old age.

John Day, son of Betty Parker and Oscar Day, died on April 5, 1921, of chronic parenchymatous nephritis in Stafford County. He was supposedly 79 years and 5 days old. He is buried at Shiloh Church, a historic black church in Stafford, where other black people with ties to Poplar Grove Farm have been buried. I cannot find another John Day in Stafford, and I believe this to be our John Day.

Based on information regarding John Day, it’s probable that Betty Parker Day and Austin Day were also slaves at Poplar Grove farm, but I cannot substantiate that information. William Day and Otho Day may also have been slaves, but that information is also unsubstantiated.

Henry Cooke

I have been unable to find any person in Stafford County with this name.

Mary and Isaac

I’ve searched census records for any households in Virginia with individuals named Mary and Isaac and can not find any. It’s possible these individuals were dead or had moved out of the area by 1870 or 1880. It is possible this family is the former slave group who visited Poplar Grove Farm from up north (perhaps the Washington DC area) and gifted the French family the glass candlesticks.

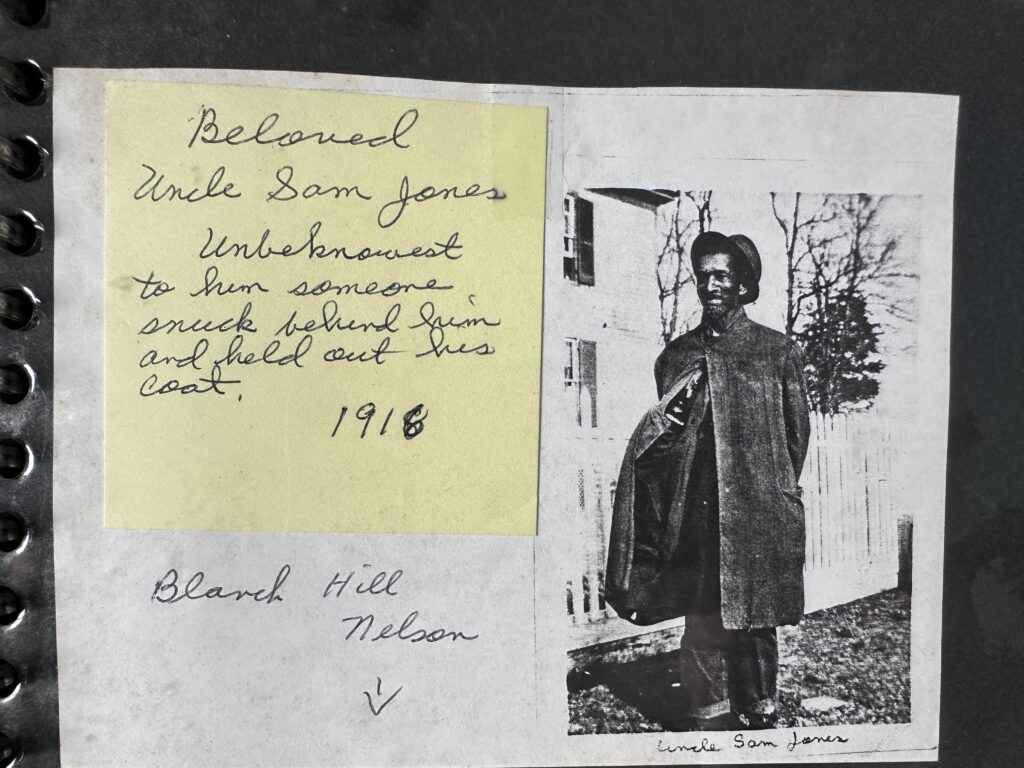

Samuel “Uncle Sam” Jones (1847 – March 12, 1934)

Sam was one of Elzy and Betty’s children. According to family stories, Sam was born very sickly and frail, and he had to be pampered in order to survive infancy. He was raised alongside James and Sally’s son, John Isemonger French, and the boys were both twelve years old when the Civil War began. (Note: Sam’s birth year is sometimes reported on the census as 1852 and in other places as 1847, which latter date matches the family lore birthdate. On the death certificate, his birth year is reported as 1844.)

Sam may have been one of the slaves James Curtis hired out in Richmond for work, but this is unclear based on the 1934 WPA interview with Sallie French Fitzhugh. If so, Sam was not even a teenager when he was separated from his mother to go work in Richmond. We have several family stories about Sam being at Poplar Grove Farm during the Civil War (ages 12-15), and I think it is unlikely Sam was among those slaves sent to Richmond.

During the Civil War, Union troops occupied Stafford County and took food and horses from Stafford families, including the Frenches. Sam helped the Frenches by hiding their horses in a swamp and feeding the horses for two weeks. Union troops did not find the horses while Sam was hiding them, but eventually they did locate the horses and stole them.

Sam always told the family that during the Civil War, James French left his home with a box that Sam believed held money, gold, jewels, and other valuables in it. James had Sam carry a shovel as they walked together towards the granary. When they reached the granary, James told Sam told to return to the house. Sam said he saw James carrying the box toward a rugged, uncultivated part of the farm known as the Devil’s Backbone and then later returned home without the box. James died in 1865 just a few weeks after the end of the war and did not retrieve the box. Despite many searches with shovels and metal detectors, nobody has ever found the Poplar Grove Treasure — it may be hidden on the Devil’s Backbone still.

According to Stafford County Marriage Records, Sam married Elizabeth “Lizzie” Hill (daughter of James and Sarriah / Sarah Brown) on September 8, 1874, when he was 22 years old. Lizzie was 23. According to her death certificate, Lizzie’s birthday was April 11, 1852. Sam and Lizzie had at least eight children: Maggie, Doc/Dock/Doctor, Samuel Welford, Betty Anne, Broaddus/Brandus, Lily Jane/Lillie, Wallace, Sadie, Elizabeth/Lizzie, and French (born approximately 1898, roughly the same time John Isemonger French helped Sam buy property for a home).

In the 1880 census, Sam’s race is listed as “mulatto” and his occupation is farmer. In 1880, Sam and his wife Lizzie were living next door to Lizzie’s family in Hartwood with their four small children and Sam’s mother, Betty Jones.

By 1900 Sam owned his own home in the area of Falmouth/Glendie. John Isemonger French helped Sam purchase this property, and the records of this transaction are on file at Stafford County Archives. In the 1900 census Sam is listed as “black”.

In the 1930 census Sam is listed as able to read and write, though all previous census records and family stories say he was unable to do so.

A family story says Sam saved Poplar Grove Farm after the death of John Isemonger French in 1906. Former slave Sam left his own young family in Falmouth and helped bring in the crops, and the family shares this story often to share how much they loved and appreciated Sam’s kindness.

In 1976, Sallie French Fitzhugh, who had known Sam well, was interviewed by Larry Evans. She shared these stories about Sam:

In an attempt to explain to me how she feels about blacks, she begins talking about Uncle Sam, a person for whom she obviously had tremendous respect and affection. It is evident not only because of what she says, but in the gentle way she talks about him.

The man she refers to as Uncle Sam was a black man who was raised at Poplar Grove Farm with Sallie Fitzhugh’s father. They were both twelve when the war began, and they would later tell Sallie Fitzhugh about tricks they would play on Union soldiers who would come to the farm to court Sallie Fitzhugh’s aunts. When the war ended Uncle Sam became a free man, and John French helped him buy a small piece of land to farm. Years later, when John French died, it was Sam who returned to run the farm for the family.

“He would stay here all week long,” says Mrs. Fitzhugh. “And go back home on weekends. And he was never treated like anybody else. he could come in the living room and would tell us all these tales.”

“And love. He was one of the finest men. Now, of course, he couldn’t read or write, but he could take, say, twenty pounds of butter. He could go to Fredericksburg an go up and down the streets and sell the butter. Two pounds one place. Three pounds another. And come back and tell you everyplace he sold it and what he got for it. He had a wondrous memory.”

As I sit listening, she goes on to tell me another anectdote about Sam. The anectdote is clealy intended to illustrate his character.

“A man went down to clean the well on a nearby farm. And he didn’t come back. Foul air. He was dead. So another man went down to try to get him out. He didn’t come back

“And, of course, they coudln’t get anybody to go down in that well. White or colored. They went far and wide.

“But Uncle Sam couldn’t refuse. He said when that woman came to him and begged him to get her son, he said he couldn’t say a word.

“So, he sent a lantern down. It went out. Then they sent buckets down. And they brought the buckets up. Bucket after bucket they hauled out. So finally when they sent the lantern down the light didn’t go out. And then he went down.

“And he said, ‘Before God, I went down singing “Nearer My God to Thee”, too.’ Mrs. Fitzhugh Sounds serious but she smiles.

“Anyhow, when he got down he said he couldn’t find the men. He said he was scared to death. They had gotten under a kind of a hollow down there. But he found them. And then he brought the bodies up.

“Now that was Uncle Sam. And, of course, he never got a dime for it.”

She goes on to tell me other anecdotes about Sam, including one about the time he resorted to a bit of trickery that Mrs. Fitzhugh found extremely funny. “They had fences in those days and you had to open the gates. As a boy, Uncle Sam was the one who dressed and rode behind the young ladies to open the gates. Of course, the other boys were very jealous and didn’t like him.”

“He said one morning he was all dressed up and sittin’ behind Miss Lou. They were goin’ somewhere. And I had an uncle that was kind of cross — I guess somethin’ had upset him. And he came out and said ‘Sam, where are you going?’ Sam said, ‘Goin’ with Miss Lou.’ My uncle said, ‘Get out here and thin corn.’

“Sam said it nearly killed him to have to work out in that front field. All the others were pokin’ fun at him and teasin’ him and all.

“And after awhile, he said, he put his head up and said ‘Yaaaassssummmmm!’ He said ‘Ol Miss [Sarah “Sallie” Curtis French] is callin’ me.’ Old Miss wasn’t callin’ him, but he ran to the house. And Old Miss, of course, she kept him.

“And he said at night he and Old Miss would sit and pick seeds from the cotton — we didn’t have a cotton gin. He said when Grandma would nod head he would throw some in the fire. Wouldn’t have to do that bunch.

“He’d tell the devilish things they’d do,” she laughs.

As I sit here listening to Mrs. Fitzhugh, it occurs to me that someone with the more distant viewpoint provided by my generation can better see that Sam was simply getting by the best way he could. Sam’s generation of blacks created a self-protective demeanor that helped them make it through the day with as few problems as possible. Minor victories could be gained with such tricks and throwing some of the cotton in the fire; however, that self-protecting demeanor also helped solidify the belief by whites that blacks were happy in their subservient role.

“Most people I ever heard of loved their masters,” says Mrs. Fitzhugh in a voice that indicates puzzlement. “And if they didn’t, why were they so loyal to them afterwards? Why were they so loyal?” She sits with her right hand cupping her ear, staring directly at me, waiting for an answer that doesn’t come.

“Now, Uncle Sam told me they were much, much better off before freedom than they were when they were free. Right after the war, if a colored family didn’t have a white family that felt responsible for them, they were out of luck.

“He used to say that when you got old (as a slave), you sat in the cabin and were fed. And kept warm. You might mind the children or do a little somethin’ like that. But you were not forced to go to work. You were cared for. He said they were much, much better off.”

She continues to talk, moving her argument further into that realm of paternalism that George Fitzhugh championed a century ago….

Sallie Virginia French Fitzhugh by Larry Evans, 1976

Nobody knows what Sam would have said about slavery to Larry, as he was not interviewed. Although Sallie told Larry, “Slavery shouldn’t have happened, of course”, blaming its introduction on “Yankees”, she was an apologist for slavery, and the stories she shared always cast herself and her family in the best light.

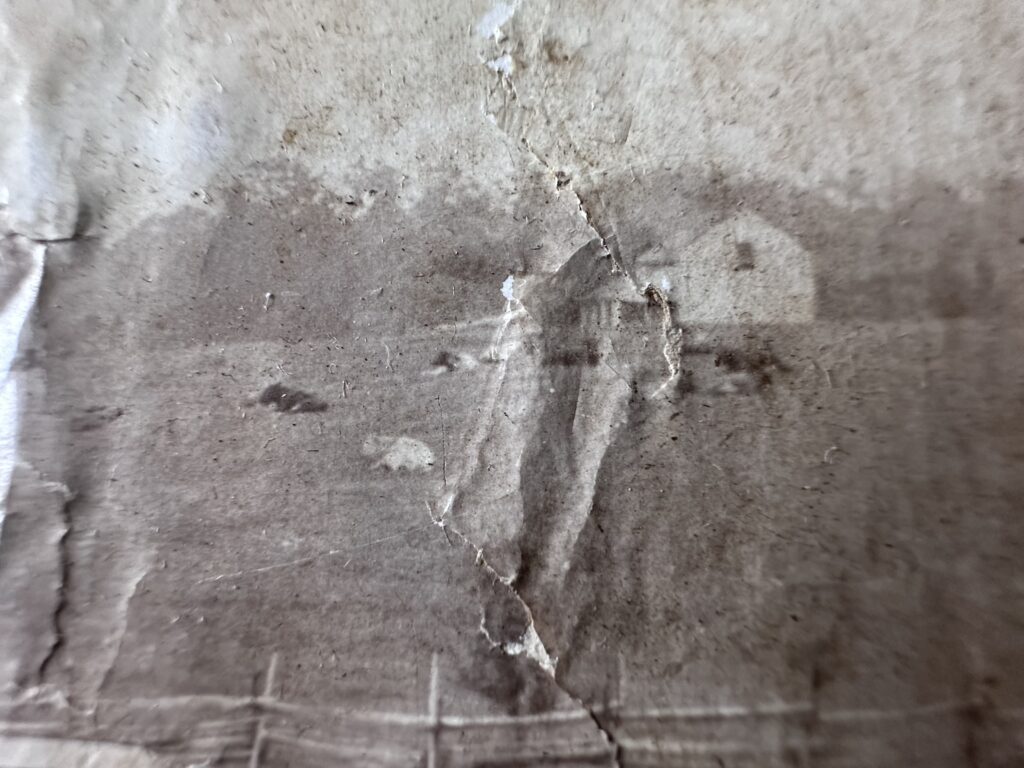

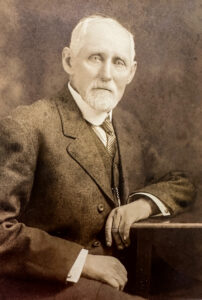

Regardless, Sam lived to be a very old man and was a close friend and respected by the French family all of his life. He lived to be more than 80 years old. We have a photograph of Sam taken when he was very old. He has a mischievous grin on his face and is wearing a long coat with a whiskey bottle in his right inside pocket. At a family request, I edited that photo and we hid the whiskey bottle in the version of the photograph we use in the family histories. I haven’t been able to find the original photo but below is a photocopy that was used in a presentation some years ago:

On March 4, 1930, Sam’s wife, Lizzie, caught the flu, which developed into bronchitis by May 15. Lizzie died on May 25, 1930, according to Virginia, U.S., Death Records, 1912-2014.

Sam became ill with the flu on February 26, 1934, the doctor visited him for the last time on March 8, and Sam died about two weeks later on March 12. His death certificate, filled out by the doctor according to a report from Sam’s son Wallace, who lived with Sam at Glendie, has a number of discrepancies (wrong birth year, calls his mother “Bell” and his wife is called Mary Hill with something illegible beside it). Sam’s death certificate says he was buried at Mount Holly Church, but I don’t know of a Mount Holly Church, and given the extreme number of errors on his death certificate, I think he was actually buried at Mount Olive Church, which is the closest black church to his home in Glendie and is where his brother, Washington, and several other family members are buried.

Sam’s stories are still remembered and shared by today’s residents of Poplar Grove Farm.

Are there any other structures dating back to slaves at Poplar Grove Farm?

The old summer kitchen is still standing in 2023 at Poplar Grove Farm. According to the 2015 Stafford County survey interview with Sally Lou Fitzhugh, this building was both lived and worked in by slaves; however, I was present for this interview and Aunt Sally Lou told the interview she didn’t know whether slaves had lived in the upper level of the two-story kitchen. The interviewer pressed Aunt Sally Lou on the issue, and finally she admitted the slaves may have lived there. I’m not sure what the interviewer’s motivation was (The Kitchen House by Kathleen Grissom was popular at the time), but Aunt Sally Lou’s “maybe” was recorded as “definitely” in the report. Slaves certainly worked in the old summer kitchen, but we don’t know if any lived inside.

The stone springhouse was built by Quakers at Poplar Grove farm and predates the French family. Slaves owned by the Frenches would have used the springhouse for their water supply, storing perishable items like butter, and for other work-related duties. The springhouse still provides water to the farmhouse and barn.

Charles French, brother of James French, also owned slaves and lived at Poplar Grove Farm. The home he built and lived in and the surrounding property was sold to the Stearne family in the 1970s. The Stearnes restored the home in 1990-2000s, and the home is still standing in 2023. It was sold and is part of the Poplar Estates subdivision now on the east of Poplar Road.

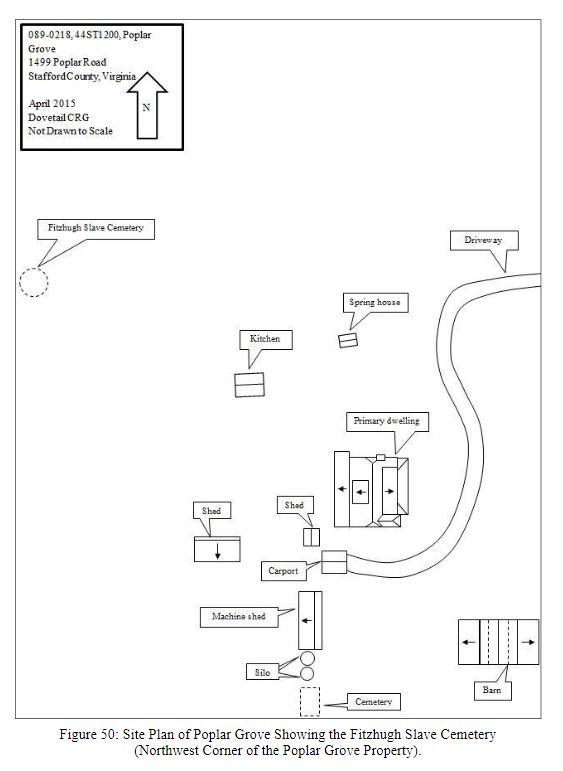

Where were slaves buried at Poplar Grove Farm?

Slaves were buried in a cemetery west-northwest of the main house on a sloping hill that faces east. This cemetery has remained uncultivated since the mid-1800s. Slave graves are marked with large stones. These graves often have a large headstone and smaller footstone nearby oriented toward the east, showing the approximate height of the individuals buried in each plot.

Did any black people continue to live on the farm after Emancipation?

At least one former slave family, the Parkers, rented a home on Poplar Grove Farm after the War according to the 1870 census. This family is incorrectly recorded as the “Harkers” in the census. I have verified the error by checking later census records. The census lists Nellie Harker (Parker), age 30; Elizabeth Harker (Parker), age 12; Hannah Harker (Parker), age 10; Jennie Harker, age 5 (Parker); and Louisa Harker (Parker), age 1.

It is probable that the Parkers lived in the home pictured above behind the barn located on Cabin Hill, no longer standing.

What relationship do the black Fitzhughs of Stafford County have to Poplar Grove Farm?

There is no relationship between the black Fitzhughs of Stafford County to the white Fitzhughs who lived at Poplar Grove Farm. These black Fitzhughs did not live or work at Poplar Grove Farm and are not related by blood to any of the Poplar Grove Farm Fitzhughs. No unrelated slave with the last name Fitzhugh ever worked at Poplar Grove Farm.

How do we know? The first Fitzhugh at Poplar Grove Farm was Lee Brockenbrough Fitzhugh (1884-1936) who married Sallie Virginia French Fitzhugh (1886-1986) in 1916, well after emancipation. Lee did not live at Poplar Grove Farm until almost fifty years after slave times. Though the Fitzhughs were slave owners, none of these slaves ever lived at Poplar Grove Farm.

Find out why Stafford County erred when they called the slave cemetery the Fitzhugh Family Slave Cemetery in 2015.

Did enslavers ever impregnate any slaves at Poplar Grove Farm?

Sort of. Charles James French (1835-1920), brother of James French, who lived on the part of the farm east of Poplar Road, did father children with at least one former slave. The French family knew of one child, who was conceived after emancipation, passed along family stories about this child and her descendants, and recently Charles’ parenthood was proven by DNA testing. Charles never married, and this child was his only offspring. He did not raise the child as his own.

If you are one of the descendants of Charles French and Jennie, you are eligible for membership in the Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia. We are all descended from a Patawomeck woman named Ontonah.

Do you know of any contact between former slaves and the French family after Emancipation?

Yes. In addition to Sam Jones’ continued close relationship with the family, a former slave family returned to the farm for a visit several years after Emancipation. Family lore has it these slaves had moved “up North,” possibly to Washington DC. These former slaves brought the family a gift: a set of glass Chinese-influenced candlesticks. These candlesticks were treasured by the family and are still at Poplar Grove Farm:

I do not know the name of the family who gifted the candlesticks to the family, and Aunt Sally Lou didn’t know either, but apparently, these former slaves had very good taste. This style of candlestick is of particular interest to people who study American arts and the Industrial Revolution. A similar set is part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection in New York City. This candlestick shows the influence of Chinese art on American design. It is an example of a new technology in the late 1800s — pressed glass — which allowed the less affluent access to inexpensive, mass-produced, beautiful pieces like this one.

The Met had these candlesticks reproduced en masse for sale in its gift shops in the 1970s. Reproductions of the candlesticks dating from this era may be purchased at Etsy or eBay in many different colors. We have photographs showing our candlesticks situated on this buffet going back into the 1950s, which substantiates the family story and shows ours are not reproductions. In addition, our candlesticks are of a slightly simpler design than the ones owned by The Met, causing us to believe our candlesticks are a less expensive version of a popular design. (More on the history of these candlesticks)

Family stories say the former slaves visited their old home at Poplar Grove Farm up until the early 1900s. At least one source says former slaves were buried in the slave cemetery even after Emancipation. Some former slaves may have visited Sarah Curtis French when she died unexpectedly while visiting her daughter in Washington, DC, as well.

Descendants of former slaves were working on the farm as paid laborers in various capacities as late as 2021.