Introduction: In August 1908, 67-year old Reverend George Stuart Hayward Fitzhugh attempted to marry a 10-year old girl, Lulu Virginia Frazier. Shortly after receiving a marriage license to wed the child, George had a heart attack, and a frantic search to determine whether he’d married the child ensued. The press reported the series of events dramatically all over the United States, while staking out Geroge’s home – even interviewing the child while she played outside and harassing the minister’s children who’d left school and work about the area to come in and help.

Fitzhugh family members dubbed the minister “Crazy George” because of the incident. While collecting newspaper clippings on the event, I discovered far more than had been shared in family stories. The newly uncovered information does not excuse George’s actions, but it does explain George’s motivations. It is important to note that while the facts seem to show that George Fitzhugh wanted to use Lulu for his own gain (care in his old age), nothing seems to indicate that George was motivated by perversion or sexual deviancy.

The story is a dramatic one that starts with a heroic female missionary, an embarrassing revelation about the General Robert E. Lee family, a trip to one of the first sanitariums in the United States, and ends with a tragic murder.

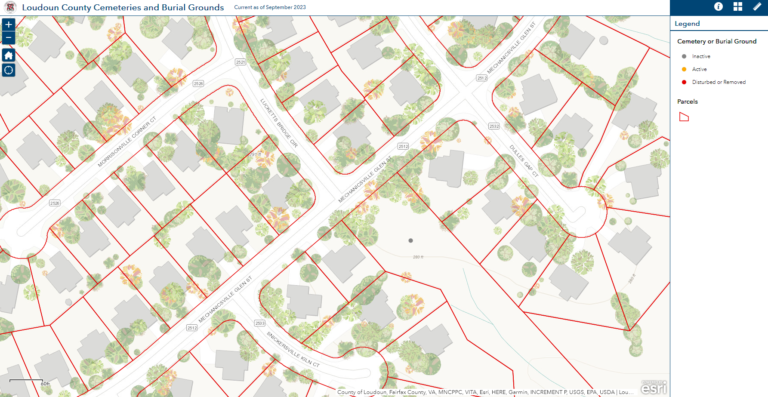

George Stuart Fitzhugh visited but never lived permanently at Poplar Grove Farm, although his son Lee, who played a minor role in this incident, did. When Lee Brockenborough Fitzhugh married Sallie Virginia French, he began a 107-year stretch of Fitzhughs living at Poplar Grove.

The People

According to one contemporary press report, the Reverend Doctor George Stuart Hayward Fitzhugh (1844-1925) was “a man of culture and has had some prominent charges in the thirty-seven years he has been a minister. He was born in Port Royal, Virginia, and is a son of George Fitzhugh, who was a well-known writer. In his youth he was a brilliant scholar. After finishing at the Episcopal Seminary at Alexandria, Virginia, he took a three-year course at the Hartford Theological Seminary. He had several prominent charges in southern Florida where he owns a large plantation.” George was living on Church Street in Curtis Bay, Maryland, with his daughter Angelina “Lena” Fitzhugh in 1908 at the “pretty ivy-covered brick parsonage … overlooking the Patapsco River”. George’s wife, Angeline Purnell Fitzhugh, had died three years earlier in 1905.

Reverend George S Fitzhugh, about 1920, family photo, Jenny Smith

Lulu Virginia Frazier (1898-1931) was a 10 year old girl living with her mother Martha Frazier at or near Mission Home, Virginia, Albemarle County, perhaps on what was then called Frazier Mountain. Lulu’s father was dead, and her illiterate mother was trying to raise her family of eleven children in difficult circumstances in the Shenandoah mountains.

The Stage

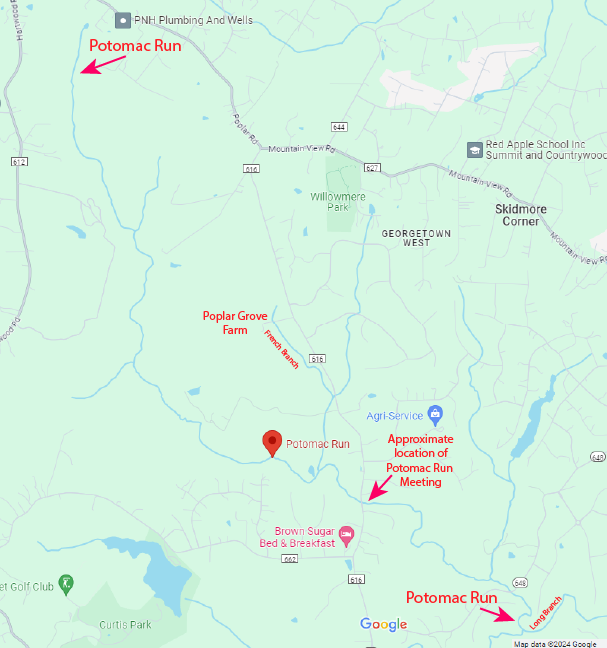

Beginning about 1890, an Episcopalian minister, Archdeacon Neve, began working in the area around Albemarle County and was informed by locals of a severely disadvantaged area. This area, Simmons Gap (later Mission Home), is near Shifflett’s Hollow and Frazier Mountain high up in what is now Shenandoah National Park on the Greene-Rockingham County line, about 3 miles north of the Albemarle County line.

The pin marked “Simmons Gap Ranger Station” is site where the Episcopalian mission was. Today’s Simmons Gap Ranger Station is the schoolhouse built in 1925. Google Maps

Simmons Gap Ranger Station is located between Rocky Mount Overlook and Loft Mountain Overlook, across from a parking area on Beldor Road, the Appalachian National Scenic Trail Trailhead Parking Area. Google Maps

Approximately 175 people lived in this area, known for “moonshine operations, backwoods justice. and suspicion towards strangers”. Apparently only two of these mountain folk knew how to read. Neve tried to help the mountain families but he made little progress. Some locals “were pessimistic and thought it was a waste of time trying to cure sinful behaviors like drinking and licentiousness among people that they viewed as not only ignorant but also primitive and untamed.”

Undaunted, Neve envisioned bringing healthcare, education, and religion to these mountain folk, beginning with a mission to be built at Simmons Gap. A family offered the use of two empty cabins, one for a school and the other to house a teacher, and so Neve began the hunt for a suitable teacher in 1900. Neve advertised in The Southern Churchman, providing full disclosure about the isolation and lack of amenities. He expected men to apply for the strenuous mission. Instead 15 women came forward. From these, 25-year old Angeline “Lena” Fitzhugh (1875-1947), daughter of the Reverend George S. Fitzhugh of Maryland, was selected, becoming the first of many women and men who taught disadvantaged mountain children at Neve’s mission schools.

Angeline “Lena” Fitzhugh, undated family photo, Jenny Smith

In November 1900, Neve presented Lena to his congregation at Ivy, and then the two traveled to Simmons Gap to assess the situation. Lena soon discovered there was no building in which to teach the previously unschooled mountain children, and her housing was to be a decrepit log cabin with missing chinking and no ready wood supply. Determined to help the disadvantaged children, Lena bravely chose to stay. Neve later wrote that he “felt like he had just been to a funeral when he left [Lena] there by herself.”

Locals America and Billy Garrison learned that the Archdeacon left Lena alone on the cold mountain. They went to check on Lena and found her struggling to start a fire on the cold stone hearth of the decrepit cabin. The couple directed her to gather her few belongings and return home with them. Money was raised, and a multipurpose building was erected at Simmon’s Gap. Lena taught school in this frame building, and a sturdy stone schoolhouse was built later in 1925.

Image with caption from National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Simmons Gap Shenandoah National Park, 2011. http://npshistory.com/publications/shen/cli-simmons-gap.pdf

Lena Fitzhugh stayed with the mission for three years until 1903, beginning an important effort to educate the disadvantaged children of Simmon’s Gap. The entire Fitzhugh family remained committed to helping the poor and stayed in contact with the Mission during subsequent years, with Lena’s father, George, preaching occasionally. In fact, it was reported the tiny church, called Holy Innocents, was under the direction of Lena’s brother, George’s son, in 1908. Lena’s brother, Edward H. Fitzhugh (1878-1955), lived in Greene County and married a mountain girl, Maggie Shifflett in 1909, showing how committed the Fitzhughs were to both loving and rescuing the mountain people.

Holy Innocent’s Church, Simmons Gap, built 1906 – image from https://www.blueridgeheritageproject.com/about-3

The work among these disadvantaged people was troubling and exhausting. It was in these circumstances, while visiting Mission Home sometime in early 1908, that the Reverend George Fitzhugh first saw the little 10-year old mountain girl, Lulu Virginia Frazier.

George Meets Lulu

Sometime in 1908, perhaps the spring time, 67-year old George Fitzhugh was the rector of St. Barnabas’s Protestant Episcopal Church of Curtis Bay, Maryland. While visit preaching at Simmons Gap where his daughter and son worked so tirelessly, George noticed Lulu. He spoke with Lulu after a church service and was impressed with the girl. George approached Lulu’s mother, Martha Frazier, and offered to adopt Lulu. After initially declining, Lulu’s mother consented for George to take Lulu with him back to Baltimore to be adopted.

In a statement to the press describing these events, George said he “loved [Lulu] since the moment I laid eyes on her,” and “thought of bringing her to my home [in Maryland] and making her my heiress”. His stated plan was to “send her to school for six years and at the end of that time she could come home and take charge of my household.”

George and Lulu then returned to Maryland to the rectory where he lived with his daughter Lena. George told Lena he intended to take care of the child, and so Lena accepted Lulu into the family and did everything possible for her comfort. George took especial care of Lulu, and later “it was said that [George] took more interest in the child than he did his own children.”

Week of August 10, 1908

Unbeknownst to his family, George went to W. W. L. Bissel, clerk of the Common Courts in Ellicott City, Maryland, to ask for a marriage license. George explained to the clerks he was old and wanted to make the girl his heir through marriage. Bissel refused to offer the license because Lulu was so young but said he’d issue the license if George returned with written permission from the girl’s parents and signatures of two reliable witnesses. George left saying he’d get the required documents.

George immediately contacted Lulu’s mother, Martha Frazier, to seek the required documents. It “is said” the mother was initially horrified to think of the marriage of her 10-year old daughter, but she did provide written consent and the signatures of reliable witnesses.

It was later reported that Mr. Deupert, clerk of the Court of Common Pleas in Baltimore, Maryland, had received correspondence from George as early as April 22, 1908, saying he was interested in the requirements for a marriage license for a man of his age and a child of age ten. Deupert told George he would not even consider such an application without affidavits from the girl’s parents, and even then, he would not issue the license without an order from the judges of the Supreme Bench. George persisted, and Deupert still refused to issue a license, even when George eventually appeared in person, explaining that he wanted to marry the girl so that she might receive his pension after his death.

Tuesday, August 19, 1908

On Tuesday, August 19, 1908, George reached out to his friend, the Reverend Snedegar, pastor of the nearby Curtis Bay Methodist Epsicopal Church, and told the Reverend he expected to marry in the morning and asked the Reverend to meet him at the courthouse at 10am to perform the ceremony without mentioning anything about the intended bride. George’s friend the Reverend happily agreed to the meeting.

Early Tuesday evening, George and Lulu snuck out of their Curtis Bay home and went to Ellicott City, Maryland, where they checked into the Hotel Howard as “Rev. George Fitzhugh and Daughter”.

Howard House Hotel, Eillicott City, 1919. Today the hotel has been made into luxury apartments. Image from https://reedbrothersdodgehistory.com/2018/06/21/then-now-howard-house-hotel-ellicott-city/

Lena Fitzhugh became alarmed that evening when she realized Lulu was missing, and she looked all over the house and yard without locating the young girl. When it became dark and Lulu wasn’t home, Lena notified several neighbors, who organized a search party. There was a wood nearby and several dangerous characters in the neighborhood, and everyone was afraid for little Lulu’s safety. When George also did not return that evening, Lena realized he must have taken Lulu with him.

Wednesday, August 20, 1908

Before 10am Wednesday morning, George and Lulu returned to the courthouse at Ellicott City. George presented the requested documents and was issued the marriage license, which was duly recorded. Mr Bisell, the clerk who had refused to give George and Lulu a marriage license the previous week, lived some distance from the office and was not present to stop the license from being issued.

Ellicott City Courthouse, about 1845, http://historichomeshowardcounty.blogspot.com/2018/02/jail-and-courthouse-underground.html

Reverend A. R. Snedegar appeared at the courthouse at 10am as agreed to wed George to his unknown bride. When he saw the girl, an amazed Snedegar wisely refused to perform the marriage, despite the license and letter showing consent of the girl’s mother and stepfather.

Reverend Snedegar said George became indignant at his refusal and offered to pay Snedegar to perform the marriage out in the country in a carriage instead of at the courthouse. Snedegar refused. Snedegar told the press later he understood that George had asked other ministers to perform the ceremony but they also refused.

George and Lulu remained away from the parsonage all afternoon, while Lena and the neighbors frantically searched for them. They finally arrived home about 6pm. It’s unclear what discussion took place, but somehow Lena discovered that George had procured a marriage license to wed the child Lulu. George obstinately refused to say whether or not he’d married Lulu. Lena, “almost hysterical”, asked her father why he’d be so foolish to marry a child, but George “only smiled and pressed the curls of the little girl who clung to his knee.”

Image of St. Barnabas Church and Parsonage, Curtis Bay, MD, from The Baltimore Sun, 22 Aug 1908, Page 7

St Barnabas and George’s home are still standing. They are now known as St Peter & Paul’s Ukranian Church located at 1506 Church Street, Curtis Bay, Baltimore, Maryland. Google Street View

Just moments later, George began to shake, grew pale, and his head fell to his chest. When Lena returned from going to get her father some water, he was unconscious, and Lena still did not know if her father had married the child!

Lena immediately contacted Doctor Thomas B. Horton, “one of the most popular and trusted men of Curtis Bay” who administered to the now insensate George. Everyone feared George would die at any moment.

Frantic inquiries were made, but nobody knew for certain whether George had married Lulu for several days.

Thursday, August 20, 1908

George’s son, George Collier Fitzhugh (1876-1921), arrived Thursday on a visit to his father and discovered to his shock that his father was attempting to marry a child and his sister was distraught.

On Thursday, while delirious or “unconscious”, George “spoke feelingly of the girl”. George thought he would die soon, and his voice was faint. He repeatedly “asked that should he die the girl be looked after with the kindest care and respect”. George’s concern over Lulu’s financial well-being continued throughout his convalescence.

Lulu reportedly took special interest in George’s illness and “hovered” near him. Lulu wept most of the day, despite Lena’s efforts to comfort her. Although Lulu was aware that Georgewas near death, she did not fully grasp what was happening around her.

The family still didn’t know if George had married Lulu, so they contacted virtually all of the ministers in Ellicott City to find out if one had performed the ceremony. The responses were all negative.

George remained “unconscious” until the late hours of the night. He was not expected to recover.

Friday, August 21, 1908

George remained so ill that no one dared interrogate him heavily about his actions.

At some point on Friday George began regaining consciousness for brief moments. He issued a statement to the public explaining his actions. He said he “loved [Lulu] since the moment I laid eyes on her,” and “thought of bringing her to my home [in Maryland] and making her my heiress”. He stated that his plan was to “send her to school for six years and at the end of that time she could come home and take charge of my household.”

George explained he believed that his marriage license meant only the virtual adoption of the girl, and justified his actions by making the embarrassing but true claim that “the old William Fitzhugh, of Virginia, married Miss [Tucker], aged 11, and then sent her to school until she was 18.” He explained that from this marriage all the Lees, including Robert E. Lee, are descended.

Another paper reported the statement thus:

“My procuring a license means only virtually an adoption of a very small child. By a technical marriage her state is greatly promoted, and she becomes my heir at my death.”

“Old William Fitzhugh of Eagle’s Nest, Virginia, married a Miss Tucker before she had completed her eleventh year, and kept her at school until she was sixteen years of age, and then she became his actual wife and the heir of his house.”

“From her are descended all of Gen. R. E. Lee’s children.”

While Mr Fitzhugh was writing his statement little Miss Frazier stood at the head of the bed and gently fanned him. The little girl seemed much interested in what was going on and Fitzhugh paused in his writing now and then to murmur that in case he should die he wanted the little one well cared for.

The clergyman’s friends are at a loss to account for his strange conduct. He was highly esteemed in the parish, was very charitable and did much to relieve the sufferings of poor people.

After explaining his actions, George gasped and lost consciousness again. Restoratives could not rouse him for any length of time, and Doctor Horton again told the press he believed George would not recover.

Some of the clergymen and people may have initially demanded George be punished for his actions. but it seems that church leaders determined George was not in control of his faculties and did not try to punish him. Son George Collier tried to visit Bishop Paret today in regards to George’s actions, but the bishop was out of town. By this date George Collier already wanted his father placed in a hospital or sanitarium.

George Collier Fitzhugh was interviewed by the press some time Friday. He said:

“My father has always been interested in children and he has made his home a regular orphanage.” he said. “From what I understand, all the children in the village congregate here and spend most of their time. They all seem to enjoy themselves playing around him and seem delighted in the interest he takes in them.”

“I could not conceive of his marrying one until I was told of it upon my arrival yesterday. It has certainly upset me, and my sister is almost at the point of breaking down. The strain on her, as well as upon myself, has been almost unbearable, and I am afraid it is going to result seriously. I hardly know what to do. I am needed at my business in Richmond, but I cannot leave my father in the condition he is in now.”

“I think the best place for the little girl is with her mother in Virginia. If it were possible I would take her there myself, but I cannot leave my sister here alone with my father under the present circumstances.”

“The case of the little girl is also an unfortunate one. Her father is dead and her mother, who cannot read nor write, lives in a little hut in a lonely part of Albemarle County. Her father was a poor mountaineer and when he died his family was left almost penniless. The mother was a hard working woman and often attended church where my father frequented at different times.”

“It was on one of his visits to the little church that he met the child and asked the mother to let him adopt her. He told about the advantages offered in a city and all the good it would do for her. The mother, thinking it was the best thing possible, consented, and that same evening she packed up her few clothes and left the little home.”

“To get to the nearest railroad station required a drive of about 20 miles across the mountains. Then several hour’s ride on the train and she was in Baltimore. The sights of the big city almost bewildered her at first and she was delighted with her new home. My father thinks there is nothing in the world like her, and his contant thought of her, with the other children, has caused him to become mentally unbalanced on the subject.”

Some time Friday evening, the family did not allow Lulu to be interviewed by the press, saying she’d already gone to bed, and informed reporters George might still die at any minute.

Saturday, August 22, 1908

On August 22, George’s youngest son, Lee Brockenborough Fitzhugh (1884-1936) arrived from school at UVA and took the marriage license from George. The family told the press they would return the license to the issuing office in Ellicott City.

It appears that Friday or Saturday, reporters approached the house and found Lulu outside. These reporters said Lulu was playing in the yard, romping about and hiding from inquisitive strangers while sticking her tongue out and making faces at them playfully “like the little mountaineer that she is.” She played with a little white cat and some children in the neighborhood. When asked if she’d like to marry George, she “saucily” replied, “I don’t care.” Reporters wrote Lulu plainly had no idea how close she’d come to being married, nor did she under the significance of marriage.

When asked if she knew that she was going to become Dr Fitzhugh’s wife, Lulu reportedly said, “All I know is that I went with him and had a good time. I want to go with him again because it is so nice riding on the street cars so far out in the country. He treated me so nice, too, and I would love to go with him again.”

Also on Saturday, the Rev. G. Mosley Murray, a general missionary of the diocese, consulted with the family. During the absence of the bishop, Murray was over George’s church, St. Barnabas.. Members of the family said they “believe that hard work for his parish temporarily unhinged” George’s mind.

Reverend George Mosely Murray (1853-1919) image from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/60237189/george-mosley-murray

Sometime today George Collier Fitzhugh told the press “the future of his father has been arranged and that the idea of marriage had vanished from his parent’s mind.” This, however, proved to be wishful thinking.

Doctor Horton consulted with Doctor Frederick T. Robinson for two hours Saturday before determining that George should be sent to an asylum.

Sunday, August 23, 1908

No church services were held at the little church of St Barnabas while its rector, George, was incapacitated. The church remained closed for some time until a new rector could be appointed.

The family remained distraught over George’s condition. George’s daughter Mary Padgett was very concerned over her father’s illness and the sensation created. Dr Horton declared that “Rev. Mr. Fitzhugh is a complete wreck physically and mentally, and that because of his age he will be fortunate if he recovers.”

The plan developed by the family and doctors was to transfer George to Spring Grove Sanitorium Sunday at 10:00 am by ambulance. Despite George’s resistance, eventually Doctor Horton was able to persuade George to recuperate at storied Spring Grove Sanitorium, which is the second oldest psychiatric hospital in the United States. Lee Fitzhugh, who was a law student at the University of Virginia, and George’s eldest son, George Collier, escorted the “tottering old man” to Spring Grove to be treated for “mental derangement”.

The scene as the “feeble and barely able to walk” George was taken to the sanitarium was described by the newspaper thus:

Looking years older than he did last week before his attack of heart trouble, and fully realizing that he was on his way to an asylum, the clergyman nearly collapsed from weakness as he was being helped into the ambulance.

Many of the neighbors had gathered when the ambulance approached the house, and by the time the old man was brought out there was a large crowd. When young Lee Fitzhugh raised his father up for a last look, hats were doffed. The scene was pathetic, as he had endeared himself to many in the little village by his acts of charity.

During the whole scene little Virginia Frazier was conspicuous by her absence. But her sobs could be heard through an open window as Miss Lena Fitzhugh tried to comfort her little charge.

When the proposition to go to an asylum was first broached to Fitzhugh by his physician, he violently opposed the idea and insisted he would not go, but the physician finally persuaded his patient that it would be far better to go to Spring Grove and be cured that to say at home in his present condition.

Dr. Horton tonight said he believed Fittzhugh would be much benefited by his staying in the asylum and would come out cured. He has been under a great mental strain for some time, and the fact that he has broken down should cause no surprise to anyone who knew him.

Despite all this, George continued to argue he was correct in seeking to marry the child. “A few hours before he was taken to the asylum [George] told Dr. Horton that he was willing to marry the child, and “would marry her yet if his family did not object”.”

Spring Grove Asylum for the Insane is the second oldest mental hospital in the United States – https://health.maryland.gov/springgrove/phototours/Pages/history.aspx

Monday, August 24, 1908

Lulu was escorted back to her home in Albemarle County, Virginia, either by George’s daughter Mary Padgett or Lena Fitzhugh, perhaps both. Lulu said she was happy to go back to live with her family, but she hoped to come back to the parsonage as she’d made friends among the village children. George Collier returned to his home in Richmond, and Lee returned to school at UVA.

Also on Monday, George was evaluated and judged insane by Spring Grove authorities.

Aftermath

George eventually did recover from his heart attack and whatever disorder that caused him to want to marry little Lulu Virginia Frazier. He lived for another 17 years and was well enough to get back to work preaching in Virginia. His children kept him close, and for some time he lived in Fredericksburg, Virginia, near his son Lee. Eventually the Fitzhughs moved, seeking their fortunes, to the newly built dam of the Tennessee River at Sheffield, Alabama, near Muscle Shoals. George passed away in Alabama with his daughters, Mary and Lena, and son, Lee, nearby.

Lulu, it seems, lived a tragic life. After returning to her family and the desperate situation near Mission Home at Simmons Gap, Lulu eventually married Thomas L. Shifflett of Albemarle County at age 19.

Lulu V Frazier and husband Thomas Shiflett – https://www.shiflett-klein.com/Lula_Shiflett_murder.htm

Lulu and Thomas had three children when she and Thomas separated. Thomas’ second cousin, Battle Shifflett, was a violent man who had become infatuated with Lulu after they’d had some sort of romantic relationship. On August 8, 1931, Battle entered the Jefferson Cafe in Charlottesville, Virginia, where Lulu worked, and engaged her in conversation. He left and bought a gun at a nearby hardware store and returned shooting, striking Lulu once. Lulu ran into the kitchen seeking protection from kitchen staff. Battle followed her into the kitchen and shot Lulu four more times. Lulu was paralyzed from one of those bullets, which lodged in her spinal column. She died shortly thereafter, but was initially able to speak and identify her shooter. Battle went on the run, but he was eventually apprehended and convicted. He narrowly avoided the electric chair and was freed from prison in the 1970s. Battle died in 1976.